Former quarterback’s stand is a reminder the injustice highlighted by raised fists 50 years ago has not gone away

Last week Colin Kaepernick became one of eight new recipients of the W E B Du Bois Medal, presented by Harvard University to those it considers to have made significant contributions to African‑American history and culture. The award, of which recipients have included Maya Angelou, Quincy Jones, Muhammad Ali and Ava DuVernay, is named after the writer and civil rights pioneer who explored the notion of “double consciousness”. Du Bois, the great‑great‑grandson of a slave, believed that being black and being American could be conceived “as leading neither to assimilation nor separatism but to proud, enduring hyphenation”.

Receiving the award, the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback spoke of the young people he hoped to inspire. “It’s not only my responsibility but the responsibility of all people that are in positions of privilege, in positions of power, to continue to fight for them and uplift them, empower them,” he said. “Because if we don’t, we become complicit in the problem.”

And yet, although he may have a much prized honour, Kaepernick is still out of a job. The NFL’s rich team owners, acting in line with America’s commander in chief, have made sure of that.

It is two years since Kaepernick first sat down during the US national anthem before a pre-season game, afterwards telling curious reporters: “I’m not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

The quarterback was wearing the colours of the 49ers, whom he had led to the Super Bowl in 2013. In the fourth and last pre-season game he acted on a suggestion that, instead of sitting, he should go down on one knee during the anthem, describing it as a sign of respect as well as a protest on behalf of the Black Lives Matter movement. The gesture caught on with other NFL players but it aroused a furious response from the soon-to-be-elected president of the United States, who, once he was in power in 2017, called upon the NFL team owners to fire players who followed Kaepernick’s example.

Donald Trump was making an early move in his efforts to tear the scabs off America’s racial wounds. It is a policy he has subsequently pursued by thought, word and deed, praising neo-Nazis while making only the rarest and most grudging acknowledgment of the contribution made by black people to American life.

Kaepernick’s honour came a few days before Tuesday’s 50th anniversary of an event in which two African‑American sporting figures took it on themselves to play a part in the civil rights struggle. Unlike Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her seat to a white person was witnessed by only a handful, or even Kaepernick, Tommie Smith and John Carlos made their gesture in an arena that could not have been more public.

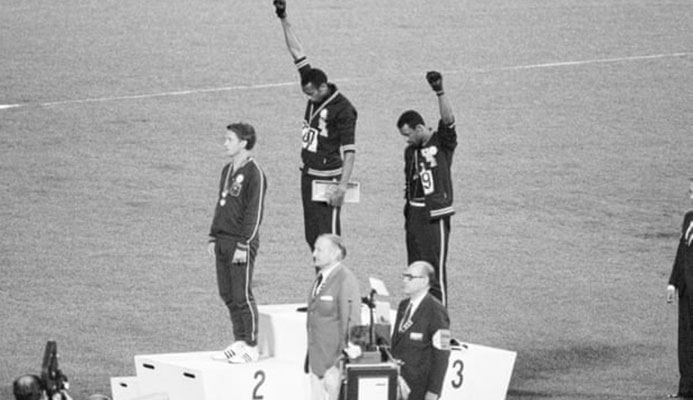

If you were old enough to watch the two black sprinters mount the Olympic podium on 16 October 1968, you are unlikely to have forgotten the experience – the jolt, the thrill – of watching them raise their fists in the Black Power salute as they stood, their heads slightly bowed, having turned to face their nation’s flag as the Star-Spangled Banner was played at the conclusion of the medal ceremony following the 200m final in Mexico City.

Each of them wore a black leather glove on his raised fist: Smith on his right, Carlos on his left. With them stood a lone white man, Peter Norman of Australia, the silver medal winner. It was Norman who, on hearing that Carlos had left his gloves in the athletes’ village, suggested that they shared the single pair, which seemed to add to the symbolism.

In the electrifying power of a moment that helped define 1968 as a year of worldwide political and cultural uprising, not many noticed that the two men in USA tracksuits were shoeless, with black socks on their feet, representing poverty. Smith also wore a black scarf, while Carlos put a necklace of beads around his neck – standing, he said, “for individuals that were lynched or killed and that no one said a prayer for”.

They were booed in the stadium and reviled in the next day’s newspaper columns. “Black America will understand what we did tonight,” Smith said, and perhaps white America did, too, but with a very different response. Avery Brundage, the antisemitic, anti-communist president of the International Olympic Committee, who had led a successful fight against the proposed US boycott of Hitler’s Berlin Games in 1936, ordered the team’s managers to send them home, where they received the first of many death threats from white supremacists. Under surveillance by the FBI, unable to find work, both struggled for more than a decade before their rehabilitation began.

Now they are key figures in the history of the modern civil rights struggle, alongside Parks, Ali, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Angela Davis. The latest member of that pantheon is more fortunate than Smith and Carlos in that he earned millions of dollars from his playing career and has the backing of a shoe company with a history of turning controversy into advertising campaigns. But by making his own silent, dignified protest against an evil that, as Smith and Carlos mounted the podium half a century ago, we imagined to be on its way to certain defeat, Kaepernick helped to remind us it has only been hiding away, waiting for its time to come again.

Since you’re here…

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important because it enables us to give a voice to the voiceless, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It’s what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as £1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.